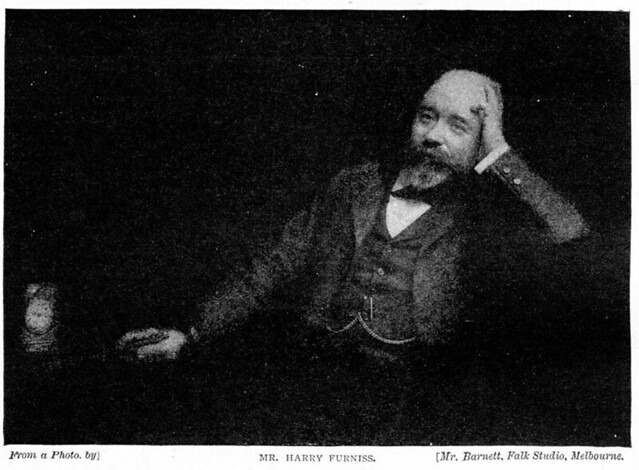

The book these ‘confessions’ are extracted from is available to read on the Internet Archive. As you can gather from the article, Harry Furniss was an author and artist, but primarily an illustrator, particularly for Punch in the late Victorian period. I found some of the anecdotes interesting (particularly the one about Gladstone having missing fingers which were never represented in caricatures).

The “Confessions” of Mr. Harry Furniss, which are to appear in two handsome volumes in the course of the present month, comprise the richest assortment of personal experiences, anecdotes, gossip, and good stories about well-known people that has been set before the public for many a long day. We have made arrangements to quote from the advance sheets of these volumes for the entertainment of our readers, and to reproduce a selection from their scores of illustrations. We should like to recount at length the very interesting narrative of Mr. Furniss’s early life and experiences, but in these pages we must be content with a few characteristic specimens of his work with pen and pencil, which may be left to tell their own story without comment.

A SPECIMEN ANECDOTE.

The poor Saxon “towrist”–what he may suffer in the Emerald Isle! There is a story on record of three Irishmen rushing away from the race meeting at Punchestown to catch a train back to Dublin. At the moment a train from a long distance pulled up at the station, and the three men scrambled in. In the carriage was seated one other passenger. As soon as they, had regained their breath one said:–

“Pat, have you got th’ tickets?”

“What tickets? I’ve got me loife; I thought I’d have lost that gettin’ in th’ thrain. Have you got ’em, Moike?”

“Oi, begorrah, I haven’t.”

“Oh, we’re all done for thin,” said the third. “They’ll charge us roight from the other soide of Oireland.”

The old gentleman looked over his newspaper and said:–

“You are quite safe, gintlemen; wait till we get to the next station.”

They all three looked at each other. “Bedad, he’s a directhor–we’re done for now entoirely.”

But as soon as the train pulled up the little gentleman jumped out and came back with three first-class tickets. Handing them to the astonished strangers, he said, “Whist, I’ll tell ye how I did it. I wint along the thrain–‘Tickets, plaze; tickets, plaze,’ I called, and these belong to three Saxon towrists in another carriage.”

TOOLE’S PENCIL.

Sir Henry Irving, like his dear old friend Mr. J. L. Toole, found relief in occasional harmless fun. Toole, however, was irrepressible.

I was one day walking with him in Leeds (where he was appearing in the evening on the stage and I on the platform). A street hawker proffered the comedian a metal pencil-case for the sum of a halfpenny. Toole made this valuable purchase. As soon as I left the platform that night I found a note for me, inviting me to the theatre directly after the performance. Toole came back on to the stage and, making me an elaborate and complimentary speech, referring to me as “a brother artist in another sphere,” etc., presented me with the pencil! I made an appropriate reply, and we went to supper.

The following paragraph from the pen of Mr. Toole appeared in the Press the next day in London as well as in the provinces:–

“Brother artists, even when working in different grooves, do not lack appreciation of each other’s work. After Mr. Harry Furniss’s lecture in Leeds the other night he and Mr. Toole foregathered; and the popular and genial actor presented the ‘comedian of the pencil’ with a very neat and handsome pencil-case, just adapted for the jotting down, wherever duty takes him, of those graphic sketches with which the caricaturist amuses us week by week.”

JAMES PAYNE.

I recollect, when I first saw him in Waterloo Place, I had just read an article of his in which he gave a recipe for getting rid of callers, which was to bring the conversation to an abrupt termination, say absolutely nothing, but steadfastly stare at your visitor until he left. I can vouch for its being a simple and effective plan.

When I entered his editorial sanctum the genial essayist received me most cordially, and looked the picture of comfort, surrounded as he was by a heterogeneous collection of pipes. Presently he knocked the ashes out of his finished pipe and mutely stared point-blank at me till I, like the pipe, went out also. But before making my exit I reminded him that I had read the article I refer to, and up to which he was no doubt acting, and that I was pleased and interested that he practised the doctrine he preached. Possibly this remark of mine was unexpected, and therefore somewhat disconcerted him for a moment, for he quickly replied, “Not at all! Not at all! Fact is, I was rather upset before you came in by a miserable man who called to see me, and at the moment I was, a propos of him, thinking of a funny story about Theodore Hook I came across last night I never heard of before. Poor Hook was at a smart dinner one evening, but instead of being as usual the life and soul of the party, he proved the wet blanket on the merry meeting, despite the fact that he, in all probability, had imbibed his stiff glass of brandy to get him up to his usual form before entering the house at which he was entertained. This most unusual phase of Hook’s character surprised everybody present, so much so that his host ventured to remark that the volatile Theodore did not seem so merry as usual.

“‘Merry? I should think not! I should like to see anyone merry who has gone through what I have this afternoon!’

“‘What was that?’ asked everyone, with one voice.

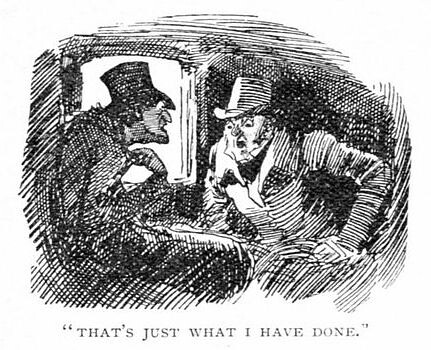

“‘Well, I’ll tell you,’ said Hook. ‘I have just come up from York in the stage coach, and I was rather late in taking my seat; the top was occupied to the full, so I had no alternative but to become an inside passenger. The only other occupant of the interior was a melancholy individual rolled up in a corner. He had donned his greatcoat, the collar of which was turned right up over his ears. He stolidly sat there, never uttering a word, until I became fascinated by his weird appearance. By-and-by the sun sank below the western horizon, the inside of the coach became darker and darker, and more ghastly seemed the cadaverous stranger as the blackness increased. The strain was too much for me. I could not keep silent another minute.

“‘”My good sir,” I said, “what ever is the matter with you?”

“‘”I’ll tell you,” he slowly muttered. “Some months ago I invested in two tickets in a great lottery, but when I told my wife of the speculation I had indulged in she nagged and nagged at me to such a frightful extent that at last I sold the tickets.”

“‘”Well?”

“‘”Well, do you know, sir, to-day those two numbers won the two first prizes, and those two prizes represent a sum of money of colossal magnitude!”

“‘”Goodness gracious me!” I shouted. “If that had happened to me it would have driven me to desperation! In fact, I really believe that I should have been frantic enough to have cut my throat!”

“‘”Why, that’s just what I have done!” replied the stranger, as he turned down his collar. “Look here!”‘”

AN APT QUOTATION.

A stoutly-made little fellow of eight, to his mother, who happened to be extremely thin: “Oh, mother, I do believe you must be the very sweetest woman in the world!”

“Thanks, very much, Lawrence. But why so affectionate? What do you want?”

“I don’t want anything. I only know you must be the very sweetest woman in the world.”

“Really, you are too flattering. Why this sudden outburst of affection?”

“Well, you know, I’ve been thinking over the old, old saying, ‘The nearer the bone the sweeter the meat.'”

ARTIST’S MODELS.

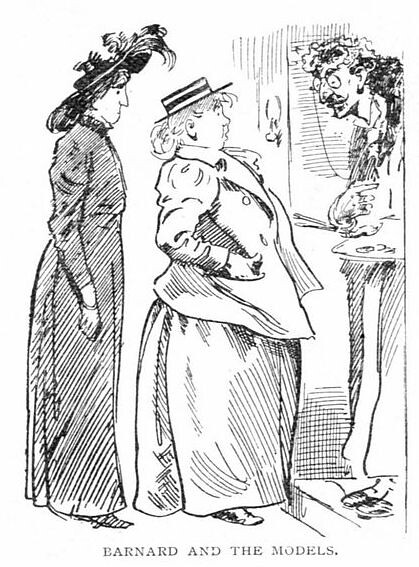

There are a number of girls who go the round of the studios, but have no right whatever to do so. They generally hunt in pairs, and this habit surely distinguishes them from the real model. They are more easily drawn than described. Two of this class once called on Barnard.

“What do you sit for? ” he asked.

“Oh, anything, sir.”

“Ah, I am a figure man–you are no use to me: but there is a friend of mine over there who is now painting a landscape–I think you might do very well for a haystack; and your friend might try-studio No. 5 and sit for a thunder-cloud, the artist there is starting a stormy piece–oh, good morning.” Tableau!

A wretched individual once called upon me and begged me to give him a sitting. I asked him to sit for what I was at work upon: this was a wicket-keeper in a cricket match bending over the wicket. I assured the man he need not apologize, as he had really turned up at an opportune moment; the drawing was “news,” and it had to be finished that day. When I had shown my model the position and made him understand exactly what I wanted, I noticed to my surprise that he was trembling all over. I immediately asked him if he were cold.

“No.”

“Nervous?”

“No.”

“Then why not keep still?”

“Well, that’u just what I can’t do, sir! I had to give up my occupation because, sir, I am hafflicted with the palsy, and when I bend I do tremble so. I only sit for ‘ands, sir–for ‘ands to portrait painters. I close ’em for a military gent; I open ’em for a bishop; but when the hartist is hin a ‘urry I know as ‘ow to ‘ide one ‘and in my pocket and the hother hunder a cocked ‘at.”

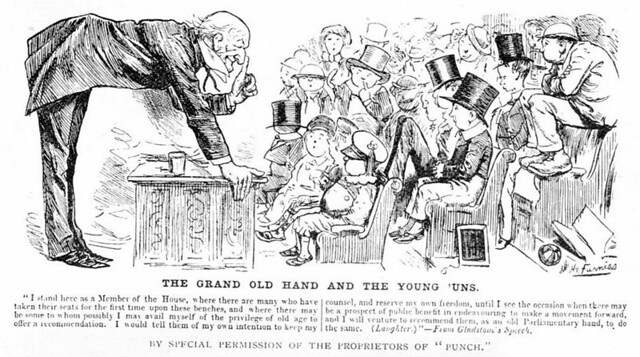

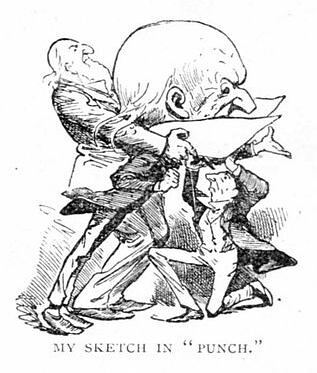

Hiding hands recalls to me a fact I may mention in justice to our modern English caricaturists. We never make capital out of our subjects’ deformities. This I pointed out at a dinner in Birmingham a few years ago, at which I was the guest of the evening, and as I was addressing journalists I mention this fact in justice to myself and my brother caricaturists. It so happened that afternoon I had heard Mr. Gladstone making his first speech in the opening of Parliament, 1886, after being returned in Opposition. Turning round to his young supporters, he used for the first time the now famous expression, “an old Parliamentary hand,” holding up at the same time a hand on which there were only three fingers. Now, what if I had drawn that hand as it was minus the first finger, showing the black patch? It would have been tempting on the part of a foreign caricaturist, because it had a curious application under the circumstances. (But it would be noticed that in my sketch in Punch the first finger, which really did not exist, is prominently shown.) This was the first time the fact was made public that Mr. Gladstone had not the first finger on the left hand; since then, however, all artists, humorous or serious, were careful to show Mr. Gladstone’s left hand as pointed out by me.

Now, I had noticed this for years in the House, and I hold as an argument that men are not observant the fact that members who had sat in the House with Mr. Gladstone, on the same benches, for years, assured me that they had never noticed his hand before I made this matter public. So that when I am told that I misrepresent portraits of prominent men I always point to this fact.

Mr. Gladstone was careful to hide the deformity in his photographs, but in his usual energetic manner in the House the black patch in place of the finger was on many occasions in no way concealed.

A DISAGREEABLE NEIGHBOUR.

The first house I occupied after I married faced one occupied by a well-known and worthy, fiery-tempered man of letters, and it so happened that one evening my wife and I were dining at the house of another neighbour. We were gratified to learn that our celebrated vis-a-vis, hearing we had come to live in the same square, was anxious to make our acquaintance. On our return home that night we discovered the latch-key had been forgotten, and unfortunately our knocking and ringing failed to arouse the domestics. It was not long, however, before we awoke our neighbours, and a window of the house opposite was violently thrown open, and language all the stronger by being endowed with literary merit came from that man of letters, who in the dark was unable to see the particular neighbours offending him, and he referred to my wife and myself in a way that could not be passed over. A battle of words ensued, in which I proved the victor, and my neighbour beat a hasty retreat. Before retiring I wrote a note to our friend we had just left to say that under the circumstances I refused to know my neighbour, and he had better inform him that I would on the first opportunity punch his head. By the same post I wrote for a particular model–a retired pugilist. As soon as he arrived next morning I placed him at the window of my studio facing the opposite house, now and then sending him down to the front door to stand on the footstep to await some imaginary-person, and to keep his eye on the house opposite. I went on with my work in peace. Presently a note came:–

“Dear Furniss,–Your neighbour has sent round to ask me what you are like. He has never seen you till this morning, and he is frightened to leave his house. He implores me to apologize for him.”

He departed from the neighbourhood shortly afterwards.

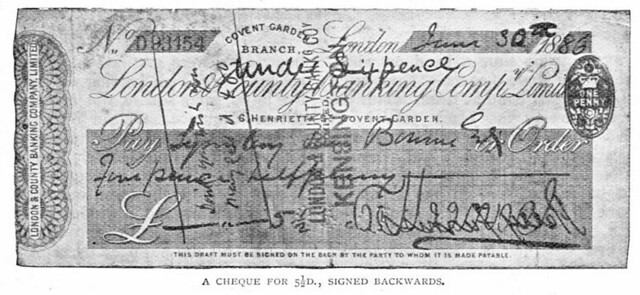

A REMARKABLE CHEQUE.

It is bad enough to purposely puzzle the overworked letter-carriers–they are too often tried by unintentional touches of humour emanating from the most innocent and unsuspected members of the public–but I confess that I was once the innocent cause of Mr. Sambourne trying the same thing on with the overworked bank clerk.

I sent my Punch friend a cheque, here reproduced, for the sum of 5 1/2d., payable to “Lynnlay Sam Bourne, Esqre.,” signed by me backwards, crossed “Don’t you wish you may get it and go?” Sambourne indorsed it “L. Sam. Bourne,” and sent it to his bank. The clerk went one better, and wrote “Cancelled” backwards across my reversed signature. It passed through my bank, and the money was paid. This is probably unique in the history of banking.

A propos of writing backwards, in days when artists made their drawings on wood everything of course had to be reversed, so writing backwards became quite easy. To this day I can write backwards nearly as quickly as I write in the ordinary way. One night at supper I was explaining this, and furthermore told my friends that they themselves could write backwards–in fact, they could not avoid doing so. Not, of course, on the table, as I was doing, but by placing the sheet of paper against the table underneath, and writing with the point upwards. Perhaps my readers will try–and see the effect. For encouragement, above are a couple of first attempts on that particular evening.

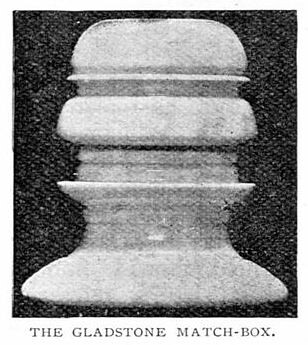

A GLADSTONE MATCH-BOX.

Mr. Gladstone’s portrait has been adopted by others besides caricaturists. It is carved as a gargoyle in the stonework of a church, and the head of the Grand Old Man has been turned into a match-box. The latter I here reproduce. It was shown to me one evening when I was the guest at the Guards’ mess at St. James’s Palace. A clever young Guardsman, who had a taste for turning, worked this out in wood from my caricatures of Mr. Gladstone, and I advised his having it reproduced in pottery. The suggestion was carried out by the late Mr. Woodall, the member for the Potteries, and was largely distributed at the time the G.O.M. was politically meeting his match and thought by some to be a little lightheaded.

FURNESS AND FURNISS.

Perhaps there are not two men with surnames so similar and yet so different in every other way than that great man of business, Sir Christopher Furness, and myself. He has an eye for business, but not one for his surname–I have an “I” in my name, and two for art only. When Mr. Furness was first returned to Parliament, plain Mr., then neither a knight nor a millionaire, he asked to see me alone in one of the Lobbies of the House of Commons. He held a note in his hand, strangely and nervously–so I knew at once it was not a bank-note.

“I–ah–am very sorry–you are a stranger to me, I–a–stranger to the House. This note from a stranger was handed to me by a strange official. I read it before I noticed the mistake. It is addressed to you.”

“Oh, that is of no consequence, I assure you,” I said.

“Oh, but it is–it must be of consequence. It is–of–such a private nature, and so brief. I feel extremely awkward in having to acknowledge I read it–a pure accident, I assure you!”

He handed me the note and was running away, when I called him back. It read:–

“Meet me under the clock at 8.–Lucy.”

“I must introduce you to Lucy.”

“No, no! Not for worlds.”

But I did. Here he is.

INTRODUCTION TO “PUNCH.”

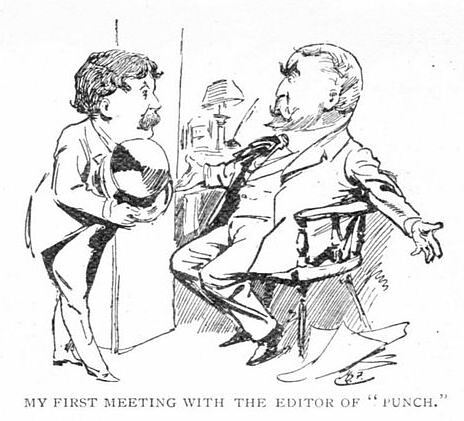

It was not until Tom Taylor had passed away that Mr. Punch would deign to give me a chance. I had then been seven years in London hard at work for the leading magazines and illustrated papers, and I may truly say that my work was the only introduction I ever had to Mr. Burnand.

When I first entered the goal of my boyish ambition–that is to say, the editorial sanctum of Mr. Punch–I had never met the gentleman who, for a number of years afterwards, was destined to be my chief, and I fully expected to see the editor turn round and receive me with that look of irrepressible humour and in that habitually jocose style which I had so often heard described. I looked in vain for the geniality in the editor’s glance, and there was a remarkably complete absence of the jocose in the sharp, irritable words which he addressed to me.

“Really,” said he, “this is too bad! I wrote to you to meet me at the Surrey Theatre last night, and you never turned up. We go to press to-day, and the sketches are not even made.”

“I don’t quite understand you,” I replied, “for I never heard from you in my life, and I don’t think that you ever saw me before.”

But surely you are Mr. —-?” (a contributor who had been drawing for Punch for some weeks). “Are you not?”

“No,” I said. “My name is Furniss, and I understood that you wanted to see me.”

This was in 1880, and from that period up to the time of my resignation from the staff of Punch I certainly do not think that I have ever seen Burnand’s face assume such a threatening and offended expression as it wore that day.

I was then twenty-six. Strange to say, Charles Keene and George du Maurier were exactly the same age when they first made their debut in Punch, but not yet invited to “join the table.”

As I was leaving my house one summer evening a few years afterwards, the youngest member of my family, who was being personally conducted up to bed by his nurse, inquired where I was going.

“To dine with Mr. Punch,” I replied.

“Oh, haven’t you eaten all his hump yet, papa? It does last a long time!” And the little chap continued his journey to the arms of Morpheus, evidently quite concerned about his father’s act of lone-drawn-out cannibalism.

DU MAURIER.

It is a curious fact that I really never had a seat allotted to me at the Punch table. I always sat in du Maurier’s, except on the rare occasions when he came to the dinner, when I moved up one. It was always a treat to have du Maurier at “the table.” He was by far and away the cleverest conversationalist of his time I ever met–his delightful repartees were so neat and effective, and his daring chaff and his criticisms so bright and refreshing.

For some extraordinary reason du Maurier was known to the Punch men as “Kiki,” a friendly sobriquet which greeted him when he first joined, and refers to his nationality. In the same way as an English schoolboy calls out “Froggy” to a Frenchman, his friends on the Punch staff called him “Kiki,” suggested by the Frenchman’s peculiar and un-English art of self-defence.

Du Maurier took very little interest in the discussions at the table; in fact, he resented informal debate on the subject of the cartoon as an interruption to his conversation, although I was informed he once suggested a cartoon which will always rank as one of the most historical hits of Mr. Punch–a cartoon of the First Napoleon warning Napoleon the Third as he marches out to meet the Germans in the war of 1870.

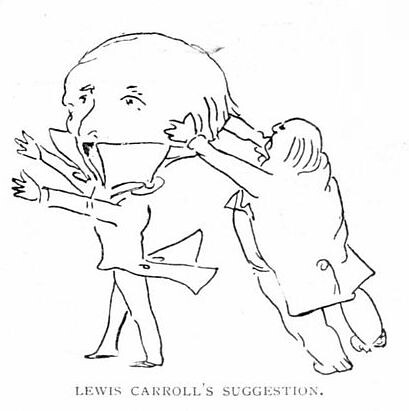

LEWIS CARROLL.

Suggestions for Punch came to me from most unexpected quarters, but were rarely of any use.

Lewis Carroll–like everyone else–got excited over the Gladstonian crisis, and Sir William Harcourt’s head to Lewis Carroll was much the same as Charles the First’s to Mr. Dick in “David Copperfield,” for I find in several letters references to Sir William. “Re. Gladstone’s head and its recent growth, couldn’t you make a picture of it for the ‘Essence of Parliament’? I would call it ‘Toby’s Dream of A.D. 1900,’ and have Gladstone addressing the House, with his enormous head supported by Harcourt on one side and Parnell on the other.”

This suggestion is the only one I adopted. Strange to say, neither Gladstone, Parnell, nor Lewis Carroll lived to see 1900.

ARTHUR CECIL.

His eccentricity was a combination of absent-mindedness and irritableness. The latter failing, he told me, would at times take complete control of him. For instance, he had to leave a train before his journey was completed, as he felt it impossible to sit in the carriage and look at the alarm-bell without pulling it. I have watched him seated in the smoking-room of the club we both attended, in which the star-light in the centre of the ceiling was shaded by a rather primitive screen of stretched tissue-paper, gazing at it for half an hour at a time, and eventually taking all the coins out of his pocket to throw them one after another at the immediate object of his irritation. He frequently succeeded in penetrating the screen, the coins remaining on the top of it, to the delight of the astonished waiters.

His eccentricity–perhaps I ought to say in this case his absent-mindedness–is illustrated by an incident which happened on the morning of the funeral of a great friend of his. As Cecil (his real name was Blount) was having his bath, he was suddenly inspired with some idea for a song; so, pulling his sponge-bath into the adjoining sitting-room, close to the piano, he placed a chair in it and sat down to try it over. A friend, rushing in to fetch him to the funeral, found him so seated, singing and playing, balancing the dripping sponge on the top of his head.

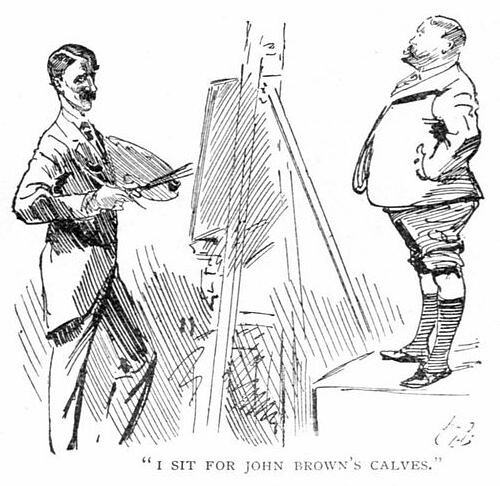

I SIT AS A MODEL.

I sat for John Brown for the picture Victoria had commissioned of Mr. Brown surrounded by her pet dogs, which she had in her private room. She was so delighted with the picture that she had a replica made of it, and placed it in the passage outside, so that it was the first picture she looked at as she left her room. Barber’s animals and children were delightful, but he was weak with his men, and was in trouble over John Brown’s calves–it was then that I posed for the “brawny Scot,” but only for the portion here mentioned.

CROSSING TO AMERICA–THE CAPTAIN OF THE LINER.

Now, this commander was a captain from the top of his head to the soles of his feet. A stern disciplinarian, erect, handsome, uncommunicative, not a better officer ever stood on the bridge of an Atlantic or any other liner. He had a contempt for the “herring pond,” and manipulated one of these floating hotels with as much ease as one would handle a toy boat. “When a navigator’s duty’s to be done” he was par excellence a modern Caesar, but despite his sternness he had a sense of humour, and his unbending moments struck one with an emphasized surprise.

He could not bear a bore. Those fussy landlubbers who are always tapping the barometers, asking questions of every member of the crew, testing, sounding, and finding fault with the weather chart, had better steer clear of the worthy captain, as, with hands thrust deep in his pockets, he strides from one end of the deck to the other during the course of his constitutional. It is on record that one of these fussy individuals, edging up to a well-known captain as he was going on to the bridge when a mist was gathering and the siren was about to blow as customary when entering on an Atlantic fog, remarked:–

“Captain, captain, can’t you see that it is quite clear overhead?”

The captain turned on his heel to ascend to the bridge, and scornfully rejoined:–“Yes, sir; yes, sir; but can’t you see that I am not navigating a balloon?”

On one occasion the captain had been through a terribly stormy afternoon and night and had not quitted his post on the bridge for one minute, the weather being awful. Fogs, icebergs, and the elements all combined to make it a most anxious time for the one man in charge of the valuable vessel and her cargo of 1,700 souls, and during the whole period the unflinching skipper had not tasted a mouthful of food. The captain’s boy, feeling for his master, had from time to time endeavoured, with some succulent morsel, to make him break his long fast; but the firm face of the captain was set, his eyes were fixed straight ahead, and his ears were deaf to the lad’s appeal. It was breakfast time when the boy once more ventured to ask the captain if he could bring him something to eat. This time he got an answer.

“Yes,” growled the captain, “bring me two larks’ livers on toast!”

These Atlantic captains of the older school were a hardened and humorous lot of navigators, and many a story of their eccentricity survives them. One in particular of an old captain seeing the terror of the junior officer during that nervous ordeal of treading the bridge for the first time with him. This particular old salt, after a painful silence, turned on the young man and said, “I like you. I’m very much impressed by you. I’ve heard a lot about you–in fact, my dear sir, I should like to have your photograph. You skip down and get it.”

The nervous and delighted youth rushed off to his cabin and informed his brother officers of the compliment the old-man had just paid him. He was in luck’s way, and ran gaily up on to the bridge, presented his photograph, blushing modestly, to the old salt.

“‘Umph! Got a pin with you?”

“Ye–es, sir.”

“Ah, see! I pin you up on the canvas here. I can look at you there and admire you. You can go, sir; your photograph is just as valuable as you appear to be on the bridge. Good morning.”

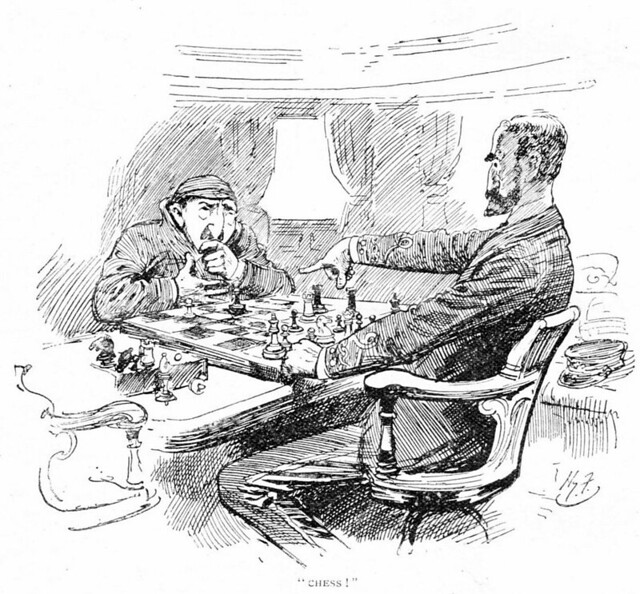

The captain of the ship I was on had his chessmen pegged, and holes in the board into which to place them, so that, despite any oscillations of the ship, they would remain in their places; but the unfortunate part of the business was that although he could provide sea-legs for his chessmen it was more than he could do for his opponent, and it was as good as a play to see Signor “Lib” hiding from the captain when the weather was not all it might be, and he in consequence felt anything but well. One mate after another would be dispatched with the strictest orders from the captain to search for the cheerless chessite; but after a time the captain’s patience would be exhausted, his strident voice could be heard calling upon the caricaturist to come forth and show himself, and eventually he might be seen en route to his cabin with the box of chessmen under one arm and his opponent under the other.

I was cruel enough on more than one occasion to follow them and witness the sequel.

“Your move, now–your move!”

“Ah, captain! I do veel zo ill! Ze ship it do go up and down, up and down, until I do not know vich is ze bishop and vich is ze queen!”

“Nonsense, sir, nonsense! Your move–look sharp, and I’ll soon have you mated!”

The poor artist did move, and quickly too, but it was to the outside of the cabin!

The captain was triumphant at table, telling us of his victory; but his poor opponent could only point to his untouched plate and to the waves dashing against the port-holes, and with that shrug of the shoulders so suggestive to witness but so difficult to describe, would thus in dumb show explain the cause of his defeat.

I remember well on one beautiful afternoon, the sky bright and the sea calm, just before the pilot came on board when we were nearing the States, Signor Prosperi (for that was his name) came up to me, his face the very embodiment of triumph:–

“Ah, I have beaten ze captain at last–but ze sea is smooth!”

MR. EDWARD LLOYD.

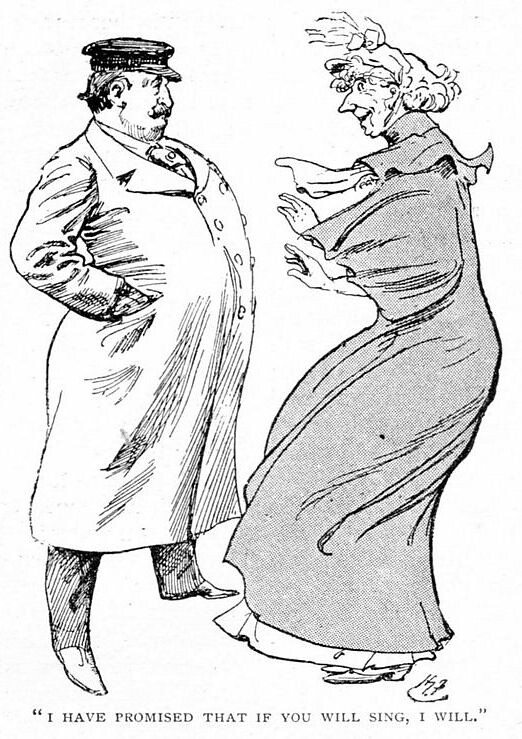

On the outward voyage we had a host in Mr. Edward Lloyd, but he was under contract not to warble until a certain day which had been fixed in New York, and no doubt his presence had a deterrent effect upon the amateur talent, with the exception of one lady, who came up to Mr. Lloyd and said:–

“You really must sing–you really must!”

“I am very sorry, madam, but I really can’t–I am not my own master in this matter.”

“Oh, but you must,” she rejoined. “I have promised that if you will sing, I will.”

AMERICAN GIRLS AND ENGLISH.

In face, I notice, the American girl is quite distinct from her English sister. I notice a difference in the way the upper lip sweeps down from the outer edge of the nostril; but more noticeable still is the fact that the cheek-bones of the American girls are not so prominent, and the smooth curve down the cheek to the chin is less broken by smaller curves. In social life the American girl charms an Englishman by her natural and unaffected manner. Our English girls are very carefully brought up, and are continually warned that this thing or that is “bad form.” As a result, when they enter society they are more or less in fear of saying or doing something that will not be considered suitable. As a matter of fact they are not lacking in energy or vivacity, but these qualities are suppressed in public, and only come to the surface in the society of intimates. American girls from childhood upwards are much more independent; they have much more freedom and encouragement in coming forward than ours. The vivacity and liberty expected of an American girl in social intercourse are considered–as I say–bad form for our girls.

The observant stranger will, if an artist, also be struck by the fact that the face of an American girl, as well as the voice, is often that of a child; in fact, if one were not afraid of being misunderstood, and therefore thought rude, one could better describe the American girl by saying that she has a baby’s face on a woman’s body than by any word-painting or brush-painting either. The large forehead, round eyes, round cheeks, and round lips of the baby remain; and, as the present fashion is to dress the hair ornamentally after the fashion of a doll, the picture is complete.

The eyes of an American girl are closer together than those of her English cousin, and are smaller; her hands are smaller, too, and so are her feet, but neither are so well-shaped as the English girl’s. Let me follow the American girl from her babyhood upwards. The first is the baby, plump, bright-eyed, and with more expression than the average English child; little older, see her still plump, short-legged, made to look stout by the double covering of the leg bulging over the boots; older, but still some years from her teens, she is still plump from the tip of her toe to her eyebrow, with an expression and a manner ten years in advance of her years, and you may take it from this age onwards the American girl is always ten years in advance of an English girl; next the schoolgirl, then that ungainly age “sweet seventeen.” She seems twenty-seven, and thenceforwards her plumpness disappears generally, but remains in her face, and the cheeks and chin of the baby are still with her.

Suddenly, ten years before the time, and in one season, happens what in the life of an English matron would take ten. The bubble bursts, the baby face collapses, just as if you pricked it with a pin, and she is left sans teeth, sans eyes, sans beauty, sans everything. This is the American girl in a hurry, and these remarks only apply to the exhausted New York, the sensational Chicago, the anxious Washington, and the overstrained child of that portion of America in a hurry.

THE TRIALS OF AN ENTERTAINER.

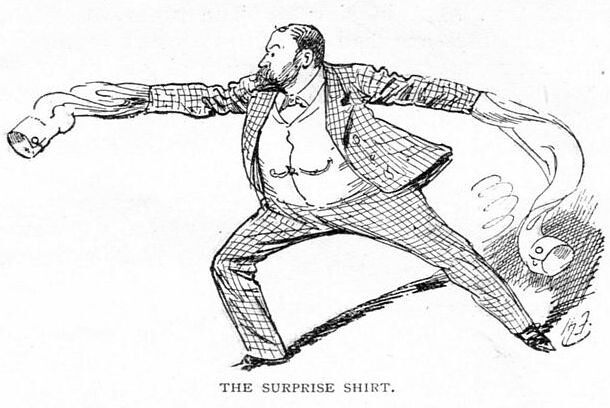

I was once obliged to deliver a “lecture” on “Art” in a rough tweed suit. It so happened that I was giving a series of lectures in the vicinity of Birmingham, and I was stopping with a friend of mine, the Curator of the Art Gallery and Museum there. He suggested my leaving my Gladstone bag, containing my change of clothes, in his office, while I spent my day rummaging about old book-shops for first editions and making calls on various friends. My host having had to go to London that day I was left to my own devices, and it was about five o’clock in the evening when I went to the Museum for my belongings. To my horror I saw a notice up: “Museum closed at three o’clock on Wednesdays,” and this was Wednesday! I rang and knocked, and knocked and rang, but all in vain. I crossed over to some other municipal buildings to see if there was anyone who could help me out of my dilemma, but my spirits went down to zero when I was there informed that the custodian of the keys lived miles out of the town. Back I went to the Museum, fiercely plotting an ascent up the water-spout or a burglarious entrance through a back window, when, to my delight, I saw an attendant gesticulating to me from a window three or four stories from the ground. My time was running very short, so I rapidly explained to him the predicament I was in, and implored him to throw my bag out of the window. He told me that he was a prisoner, locked in to look after the building, that there were three or four double-locked doors between him and the private office in which my coveted bag was lying, and wound up with the cheering announcement that my case was hopeless.

I had only a few minutes left in which to catch my train. A glance at my cuffs showed me that one’s linen has to be changed pretty frequently in a Midland town, so I made a frantic dive into a shirt-maker’s.

“White shirt, turn-down collar! Look sharp!”

“Yes, sir. Size round neck, sir?” “Oh, thirty, forty–anything you like, only look sharp!” Time was nearly up.

He measured my neck carefully. The size was a little under my estimate, so I got the shirt, bolted for the station, and jumped into the train as it was going off, my only luggage being my recent purchase. I got into this, and soon I was on the platform in my tweed suit. I apologized to the audience for making my appearance minus the orthodox costume, saying it might have been worse, and that it was better to appear without my dress clothes than without the lantern or the screen. I believe they soon forgot there was anything unusual about me, but I think that as I worked up to my subject, and became more and more energetic, they could see that I wasn’t altogether happy. That wretched shirt certainly fitted me round the neck, but the sleeves were abnormally long for me, and the cuffs being wide they shot out over my hands with every gesture. If I uplifted my hands imploringly, up they went, halfway up the screen; if with outstretched arms I drove one of my best points home, those cuffs would come out and droop pensively down over my hands; if I brought my fist down emphatically, a vast expanse of white linen flew out with a lightning-like rapidity that made the people in the first row start back and tremble for their safety; and when, after my final grand peroration, I let my hands drop by my side, those cuffs came down and dangled on the platform.

If my reader happens to be much under the medium height, and rather broad in proportion, I would warn him not to buy his shirts ready-made. I cannot understand the idea of measurement that leads a shirtmaker to cut out a shirt, taking the circumference of the neck as a basis. I know a man about six feet high who has a neck like a walking-stick. If he bought a shirt on the shirt-makers’ system it would barely act as a chest-protector; and, on the other hand, this shirt in question, as I said before, certainly fitted me round the neck, but I nearly stepped on the sleeves as I went off the platform at the close of my lecture, and some of the audience must think to this day that I am a conjurer, and that on this occasion I was going to show them some card trick with the aid of my sleeves, which would have been invaluable to the Heathen Chinee. Indeed, this is not the only time I have been suspected of being a sort of necromancer.

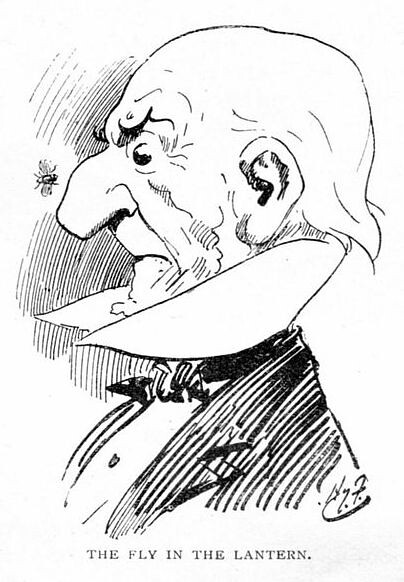

A fly was the offender on one occasion in my experience. I was showing some serious portraits of Mr. Gladstone in my entertainment, “The Humours of Parliament,” and was doing my level best to rouse an appreciative North Country audience to a high pitch of enthusiasm for the man they worshipped so. I was telling them that at one moment he looks like this, and at another moment he looks like that, when I was amazed to hear them go into fits of laughter! In describing Mr. Gladstone I dilate upon him first in a rhetorical vein, and then proceed to caricature my own delineations, and it has always been flattering to me to find that the serious portraits have been received with a grave attention only equalled by the laughter with which the caricatures have been greeted. But not so on this occasion. I spoke of his flashing eye (titters!), his noble brow (laughter!), his patriarchal head (roars!), and a mention of his commanding aquiline nose nearly sent them into hysterics! Now, in my lecturing days mishaps may have occurred which were due to some fault of the lantern or operator provided by the society I lectured to; but with the splendid set of lanterns I had made for my entertainment, engineered by the infallible professor who exhibited for me, I never troubled to look round to see if the picture was all right. But for a second it struck me that by some mischance he might be showing the caricatures in place of the serious portraits. Quickly I turned round, and the sight that met my eyes made me at once join in the general roar. There was a gigantic fly promenading on the nasal organ of the Grand Old Man, unheeding the attempts which were being made on its life by the professor, armed with a long pointed weapon. It had walked into the professor’s parlour–that is to say, into his lantern–and taken up its temporary residence between the lenses, whence it was magnified a hundredfold on to the screen!

When I give an “entertainment” I have, of course, no chairman, but when I “lecture” (which I occasionally do still) I am sometimes “introduced.”

A story is told of a distinguished irritable Scotch lecturer who on one occasion had the misfortune to meet with a loquacious chairman, the presiding genius actually speaking for a whole hour in “introducing” the lecturer, winding up by saying: “It is unnecessary for me to say more, but call upon the talented gentleman who has come so far to give us his address to-night.” The lecturer came forward: “You want my address. I’ll give it to you: 322, Rob Roy Crescent, Edinburgh–and I’m just off there now. Good-night!”

SALA’S TOES.

[The following extract requires a little explanation. Du Maurier told Mr. Furniss a story about Mr. G. A. Sala’s rejection as an Academy student owing to his sending in a drawing of a foot embellished with six toes. Mr. Furniss repeated this joke, quite good-humouredly, at a supper, which, together with some other allusions to himself which were incorrectly reported, so roused Mr. Sala’s ire that he brought the matter into the law courts, and the case excited much interest and amusement.]

Skits showing six toes were plentiful, jokes in burlesque and on the music-hall stage were introduced as a matter of course, and private chaff in letters was kept up for some time. One private letter I wrote du Maurier: “Sala has no sole for humour–you have made me put my foot in it,” and added the Six Toes signature sketch. In this no doubt du Maurier found inspiration for “Trilby.”

WHISTLER’S LOLLIPOPS.

I recollect an incident the mention of which will, I fear, send a cold shudder through any worshipper of “Nubian” nocturnes and incomprehensible “arrangements.” On one occasion after leaving the banquet of the Guild I beheld Whistler–“Jimmy” of the snowy tuft, the martyred butterfly of the “peacock room”–to whose impressionable soul the very thought of a sugar-stick should be direst agony, actually making his way homewards hugging a great box of lollipops!

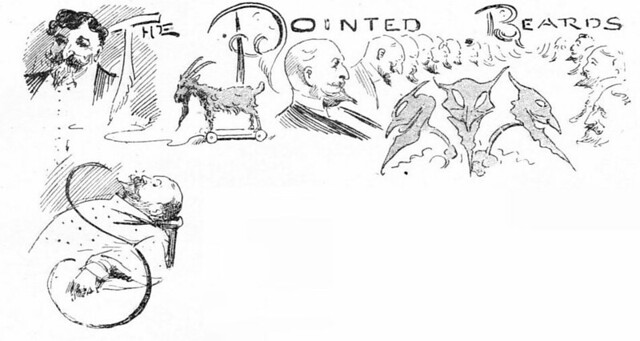

THE CLUB OF POINTED BEARDS.

It is said an Englishman will find any excuse to give a dinner, but my experience has been that this is truer of Americans. I have been the guest of many extraordinary dining clubs, but as the most unique I select the Pointed Beards of New York. To club and dine together because one has hair cut in a particular way is the raison d’etre of the club; there is nothing heroic, nothing artistic or particularly intellectual. It is not even a club to discuss hirsute adornments; such a club might be made as interesting as any other, provided the members were clever.

That most delightful of litterateurs, Mr. James Payn, once interested himself, and with his pen his readers, in that charming way of his, on the all-important question: “Where do shavers learn their business? Upon whom do they practise?” After most careful investigation he answers the question: “The neophytes try their prentice hands upon their fellow-barbers.” That may be the rule, but every rule has an exception, and I happened once to be the unfortunate layman when a budding and inexperienced barber practised his art upon me. I sat in the chair of a hairdresser’s not a hundred miles from Regent Street. I had selected a highly respectable, thoroughly English establishment, as I was tired of being held by the nose by foreigners’ fingers saturated with the nicotine of bad cigarettes. I entered gaily, and to my delight a fresh-looking British youth tied me up in the chair of torture, lathered my chin, and began operations. I was not aware of the fact that I was being made a chopping-block of until the youth, agitated and extremely nervous, produced a huge piece of lint and commenced dabbing patches of it upon my countenance. Then I looked at myself in the glass. Good heavens! Was I gazing upon myself, or was it some German student, lacerated and bleeding after a sanguinary duel? I stormed and raged, and called for the proprietor, who was gentle and sorry and apologetic, and explained to me that the boy must begin upon somebody, and I unfortunately was the first victim! I allow my beard to grow now.

Otherwise I should not have been eligible for the New York Pointed Beards, for no qualification is necessary except that one wear a beard cut to a point. The tables were ornamented with lamps, having shades cut to represent pointed beards. A toy goat, the emblem of the club, was the centre decoration. We had the “Head Barber,” and, of course, any amount of soft soap. A leading Republican was in the barber’s chair, and during dinner some sensation was caused by one of the guests being discovered wearing a false beard. He was immediately seized and ejected until after the dinner, when he returned with his music. It so happened we had present a member of the Italian Opera, with his beautiful pointed beard, and he had also a beautiful voice. But New York could not supply an accompanist with a pointed beard! So a false beard was preferred to false notes.

MY PREFACE IN BRIEF.

In these volumes, if I have made some joke at a friend’s expense, let that friend take it in the spirit intended, and–I apologize beforehand.

In America apology in journalism is unknown. The exception is the well-known story of the man whose death was published in the obituary column. He rushed into the office of the paper and cried out to the editor:–

“Look here, sur, what do you mean by this? You have published two columns and a half of my obituary, and here I am as large as life!”

The editor looked up and coolly said: “Sur, I am vury sorry; I reckon there is a mistake some place, but it kean’t be helped. You are killed by the Jersey Eagle, you are to the world buried. We nevur correct anything, and we nevur apologize in Amurrican papers.”

“That won’t do for me, sur. My wife’s in tears; my friends are laughing at me; my business will be ruined–you must apologize.”

“No, si–ree, an Amurrican editor nevur apologizes.”

“Well, sur, I’ll take the law on you right away. I’m off to my attorney.”

“Wait one minute, sur–just one minute. You are a renowned and popular citizen: the Jersey Eagle has killed you–for that I am vury, vury sorry, and to show you my respect I will to-morrow find room for you–in the births column.”

Now, do not let any editor imagine these pages are my professional obituary–my autobiography. If by mistake he does, then let him place me immediately in the births column. I am in my forties, and there is quite time for me to prepare and publish two more volumes of my “Confessions” from my first to my second birth, and many other things, before I am fifty.