Wikipedia’s article on Henry Scott Tuke has many more details of his work, and reproductions of several (including the nude bathing pictures which he is best known for these days). As is common with late-Victorian artists, most of the rest have been pretty comprehensively out of fashion for some time.

To paint the salt sea is, as Ruskin has declared, one of the most difficult achievements in the realm of art, and one which, to English eyes at least, has the most fascinating charm. For several generations the excellence of our marine art has corresponded with the greatness of our naval power, and to-day we have painters not unworthy of succession to Copley Fielding, Clarkson Stanfield, and Henry Moore, if not to Turner himself.

In Mr. J. C. Hook, R.A., these painters have a veteran whose powers, if not exhibited in all the vigour they once possessed, are at the age of eighty-five by no means exhausted. Through his long career Mr. Hook has in turn given attention to most parts of the British coast–east, west, north, and south–seeking to discover and to depict the distinctive beauty of the sea as seen from each. But the old man now takes a natural pride in recalling that he was instrumental, long ago, in bringing the North Devon and Cornwall shores into the great favour which they now enjoy with artists. Mr. Hook was the first to paint Clovelly for the Academy, which he visited before Kingsley wrote “Westward Ho!” and such pictures as “Welcome, Bonny Boat,” and “A Fisherman’s Good-night” set everybody talking of the unique beauty of this little spot. Hook went all along that coast from Bideford to Lynmouth, one of a jovial party of young artists who rode on mules and carried their food with them.

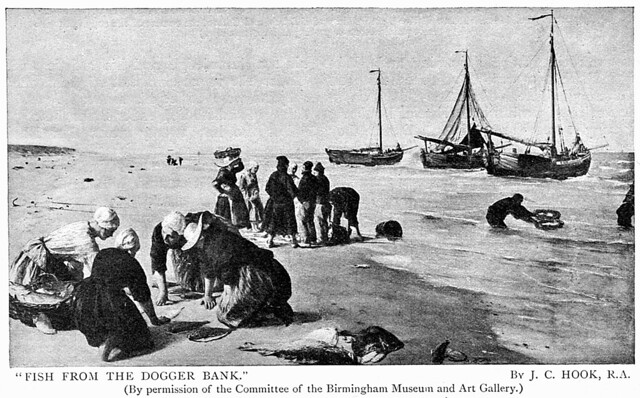

Mr. Hook’s methods are of great interest in comparison with those of the younger men to whom the sea is still giving a message of fame and success. Although his whole life, with the exception of a brief early period, has been devoted to sea-painting, he has never made his home by the sea. When he left London, nearly forty years ago, it was to settle down on the beautiful little Surrey estate, near Farnham, where it has been my delight to see him in the evening of his days, hale, hearty, and cheerful. “For one thing,” he told me, in explanation, on this occasion, “I am so fond of quietude, and, whilst enjoying the sight, I never cared for the ceaseless sound of the sea.” So every year Mr. Hook has spent his month or two on the coast, industriously painting the seas in pictures which were afterwards to be finished–as regards skies and figures–in his rural home. The example given, “Fish from the Dogger Bank,” was painted as long ago as 1870.

To facilitate the painting of the skies he had a building put up in the grounds of Silverbeck, which resembles somewhat an astronomer’s observatory and is called his “sky parlour”; with adjustable windows all round, he could paint there any part of the firmament according to the requirements of his picture. At the sea itself he has spared no pains in the study of turbulent waves and massive rocks, rowing, swimming, and climbing in all kinds of weather with the hardihood of a strong athlete. The same resolution in the service of art has been shown, I believe, by every successful sea-painter, although they have not all possessed Mr. Hook’s splendid physique. Turner had himself lashed to the rigging of a ship in order that he might know better how to paint a storm at sea.

Mr. C. Napier Hemy, A.R.A., has had the rare advantage of actual apprenticeship to the trade of the sea. Although his name is associated now with Falmouth and the Cornish coast the artist comes from coaly Newcastle, and his earliest recollections are of its ships and shipping. At the age of ten he went with his parents to Australia, and in the course of the four months’ voyage there–and back three years after–he acquired a knowledge of the rigging and other parts of a sailing-ship which he has kept throughout life. This early experience of the sea confirmed and strengthened a boyish love for it. Although intended by his parents for the Dominican priesthood, Mr. Napier Hemy always hankered after a seafaring life, and at the age of seventeen he actually ran away from Ushaw College, Durham, and took service on a collier sailing from Newcastle. After a year or two of the hardships an apprentice customarily underwent at sea in those days, he was invalided home and became a student at the Newcastle School of Art. At twenty-two the idea of entering the priesthood was definitely abandoned, and Mr. Napier Hemy resolved to make painting his profession. But it was some time before he discovered the true relationship between his sea knowledge and his artistic talent. Under the impression that religio-mediaeval subjects were to be his metier, he went to Antwerp and studied under Baron Leys.

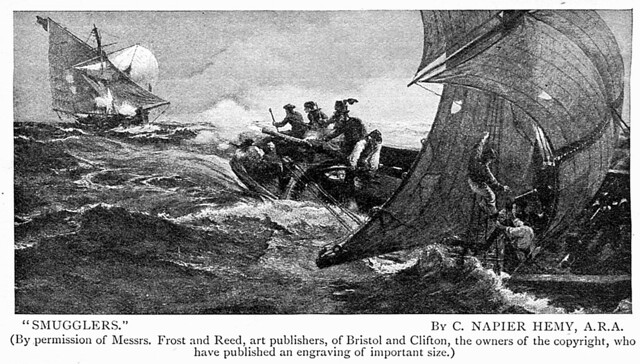

For the last twenty years Mr. Napier Hemy has resided at Falmouth, spending almost as much time afloat as ashore. If a visitor does not find him at his villa, Churchfield, he is almost certain to be on the Vandermeer, a roomy yacht, fitted with a cabin-studio, on which the artist can cruise round the harbour or explore the coast with equal safety and convenience. On this craft–and on her predecessor, the Vanderwelde–Mr. Napier Hemy has made the studies for all his out-at-sea pictures, such as “Smugglers,” “The Rescue,” and “Breakers Ahead.” In the great majority of his pictures Mr. Napier Hemy, unlike most marine artists, has obviously painted not from the standpoint of the coast, but from that of floating timbers; although “Pilchards”–the Tate Gallery picture–and “Wreckage” are conspicuous examples to the contrary. Having made his studies on the sea, Mr. Napier Hemy paints the actual picture in his studio at Churchfield, using model ships when necessary with which to ensure accuracy in various details.

Mr. Napier Hemy’s Valdermeer is now a familiar object in Falmouth Harbour, and its owner is a popular personage with the boating and fishing community, among whom he has no difficulty in finding models for the figures in his pictures. When the artist’s first craft, the Vanderwelde, was originally seen upon the waters, the purpose of this “Pickford’s van sort of a boat,” with the strange adaptation of its cabin and the conversion of some of its port-holes into windows, excited much conjecture among the old salts as they lounged about the quays, smoking their pipes. The Vanderwelde, which, like its successor, was named after a great Dutch painter, came to an untimely end in a winter storm, but with an affectionate sentiment Mr. Napier Hemy has preserved part of the wreck, and in the garden of Churchfield it still serves as a sort of studio and summer-house.

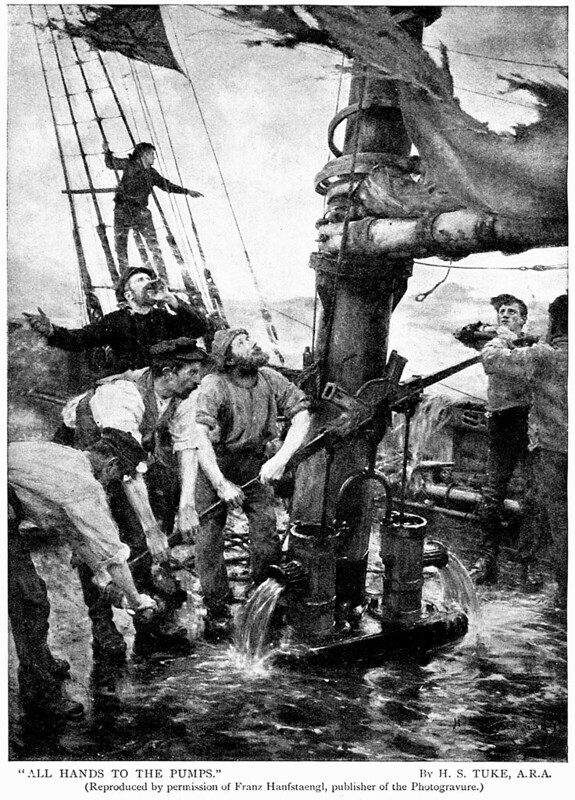

Falmouth is also the chosen home of one of Mr. Napier Hemy’s younger rivals in sea-painting, Mr. Henry S. Tuke, A.R. A. The son of a distinguished physician, a specialist in brain disease, he had no obvious destiny for either art or the sea. Nevertheless, he has a sailor’s love of salt water, and even if you see Mr. Tuke in the garden of his widowed mother’s villa at Hanwell, instead of his cottage on the edge of the high cliff of Pennance, you might easily suppose the bronzed features and sturdy, broad-shouldered figure, attired with careless ease in blue serge, to be those of an officer in our mercantile marine. Yet the course of Mr. Tuke’s life before winning his reputation as a sea-painter had been scarcely unconventional. Boarding-school at Weston-super-Mare, where the natural boy’s naval instincts, had, perhaps, a little more than the usual scope; several years’ study of art at the Slade School, London; several more in Paris and Italy; many more or less unsuccessful pictures of miscellaneous subjects–this was the record when Mr. Tuke turned his eyes to the sea, found that its beauty seemed to yield itself to his brush, and forthwith left the parental home in order to live for about nine months in a Falmouth cottage, amidst the marine scenery which, in all his journeyings, had most appealed to him by its charming variety of colour and aspect. Mr. Tuke has painted the sea in all its moods, and the picture by which his powers won general recognition was “All Hands to the Pumps,” a presentment of a fateful incident in stormy weather, which was purchased out of the Royal Academy in 1889 by the Chantrey trustees and now hangs in the Tate Gallery. But his most distinctive achievement is undoubtedly the painting of sea-bathers–scenes of healthy, vigorous enjoyment in a fairly placid sea, reflecting the deep, rich colouring of a summer sky. To Mr. Tuke’s ability in this respect the Chantrey trustees gave prompt recognition by buying–only five years after their first purchase–the picture entitled “August Blue.” In “The Swimmers’ Pool” and “The Bathers” Mr. Tuke has given us further examples of the same kind.

His success in this respect is doubtless partly due to the fact that all his studies from the nude are made actually on the spot represented in the picture. This course has sometimes necessitated somewhat severe ordeals for the models. “In ‘August Blue,'” he confesses, “I had two sets of boys, and when one set got perished with the cold they were relieved and the others went on duty.” As a rule, however, he has not called for such Spartan endurance as this. Along the Cornish coast there are many sheltered little coves where Mr. Tuke can set up his easel free from the observation of the curious, and on a hot day there is no particular hardship to his models in sitting or standing without their clothes on the sun-dried beach while the artist paints the form and flesh tints against backgrounds of white spray, quiet blue waters, and rugged grey rocks.

It ought to be said that if, in enthusiasm for his work, he is apt to be exacting from models, he does not spare himself. He is constantly afloat in all weathers in a little sailing-boat–just large enough for his painting implements and a few simple necessaries of life–which is known as the Piebox. This name was not deliberately given to the little craft by her owner, but acquired it in place of the more classical designation she originally bore from the colloquial wit of the Falmouth boatmen. Until a year or two ago Mr. Tuke was the master of a full-sized brigantine which was once the property of the French Government. She had put into Falmouth in an unseaworthy condition, and after lying there for some time was ordered by the French Admiralty to be sold by auction. Mr. Tuke bought her cheaply, but the Julie required a considerable expenditure before she could be made presentable and fairly safe for coasting trips. She served Mr. Tuke, however, faithfully for some years, until her timbers again threatened to come apart, it became perilous to take her out of harbour, and she was condemned as being this time quite irreparable.

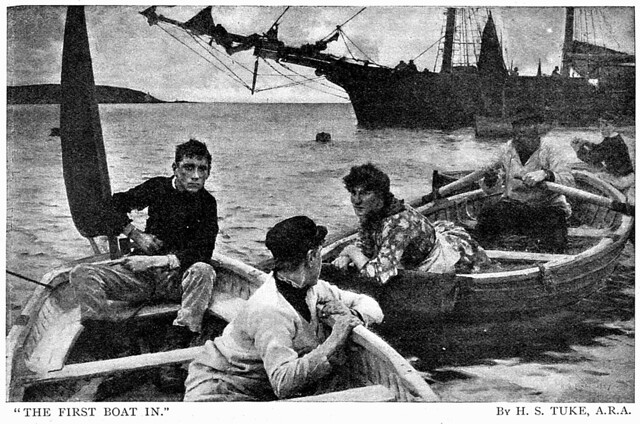

One of Mr. Tuke’s greatest difficulties in his figure pictures is in training new models. They are invariably amateurs–Cornish seafaring folk, who have but the dimmest ideas regarding art and its requirements. It is, consequently, a somewhat tedious business to teach them how to sit or stand so that they may be effectively painted, and for this reason Mr. Tuke confesses he has been tempted to use the same models for different pictures, until they have become a little familiar, perhaps, to frequenters of the picture galleries; the raw material is plentiful enough, but it requires so much welding into shape. This difficulty would certainly be greater if Mr. Tuke were not on such excellent terms with the class of people from whom his models are drawn. As an expert swimmer, a good oarsman, and an enthusiastic yachtsman–Mr. Tuke has his own racers at Falmouth, the Red Heart and the Firefly–he has the best of passports to their hearts. When he is pottering about the harbour in a fisherman’s jersey, sea-boots, and oilskins they are almost inclined to regard him as one of themselves. Of the manner in which he has painted them the following picture, “The First Boat In,” may be regarded as an excellent example.

It is in a similar sphere of work that the name of Mr. W. H. Bartlett has become favourably known at the leading exhibitions in recent years. With the exception of “Here We Go Round and Round” and one or two other pictures, however, the importance of the sea on this artist’s canvas is secondary, I think, to that of the figures. Mr. Bartlett himself, who lives as far away from the waves as Langley, in Buckinghamshire, seems to be conscious of this fact when speaking of his method of work. “Concerning such subjects I can only say that the problem of flesh-painting en plein air has always been to me a most interesting one. The ‘colour of life,’ whether seen under grey or sunny skies, is fascinating.” From this statement it may be inferred that Mr. Bartlett has painted the sea because, in relation to bathing, it affords almost the only possible background for nude figures in subjects of present-day open-air life.

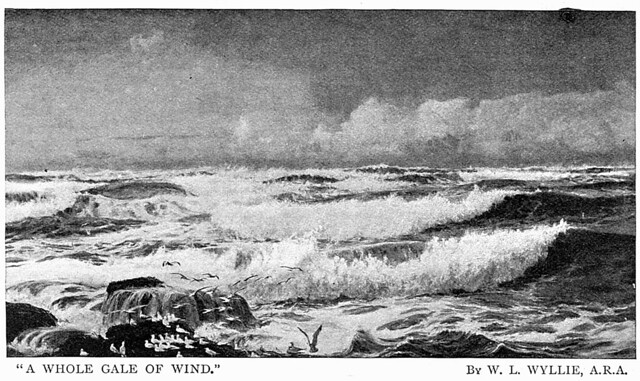

Mr. W. L. Wyllie, A.R.A., has shown equal excellence in painting both sea and river, and to Londoners “Toil, Glitter, Grime, and Wealth,” “The River of Silver,” “The River of Gold,” and other presentments of the mystical beauty of the Thames are probably the most familiar of his pictures. But Mr. Wyllie is as much at home on the sea as on the river, although a great part of his canvas is usually taken up by an immense warship, a majestic “liner,” or a graceful yacht. The picture, “A Whole Gale of Wind,” reproduced herewith, is most interesting as being somewhat of a new departure on the painter’s part in depicting merely the action of waves apart from the association of men and ships.

Although his style is largely different, Mr. Wyllie’s method of work has some resemblance to that of Mr. Tuke and Mr. Napier Hemy. He, too, has his floating studio, and although many miles from the open sea his land residence is close to the banks of the Med way, over which river it possesses an extensive view. When the visitor at Hoo Lodge is taken down to “The Dock”–a spacious boat-house in Mr. Wyllie’s own private grounds, thus invariably spoken of–the artist is apt to offer an apology for the Four Brothers, which at her moorings looks only what she pretends to be–a good, sound, and stalwart Thames barge, of one hundred and twenty tons. But on this vessel Mr. Wyllie traverses the Channel from end to end; accompanied by his wife and children he has sometimes spent weeks at sea, only putting into port for provisions and letters. The Four Brothers has a crew of two, but the painter has a certificate for navigation and is his own captain.

Mr. Wyllie has his “studio” in the roof of the cabin–a ladder seat with a plate-glass “look-out” round it, which protects him from wind and rain and enables him to work in any kind of weather. In the cabin itself there is a fixed easel, and telescopes placed in the port-holes enable him to make close observations at considerable distances. With such facilities Mr. Wyllie has made studies of the sea and of shipping in all their possible aspects–studies in black and white as well as in colour, with which many portfolios at Hoo Lodge are literally crammed. The studio at Hoo Lodge in size and arrangement does not greatly differ from those of his fellow-artists in Kensington or St. John’s Wood. But at the top of the house he has a second studio, which indicates a sort of intermediate stage in the making of a picture–between the studies made afloat and the finished canvas. It is a little room built in the roof, somewhat resembling an astronomer’s observatory, with a big telescope projecting through the window and resting on a swivel, on which it can be turned from point to point so as to command the whole view of the Medway as far as Sheerness on a clear day. Mr. Wyllie finds this contrivance most useful when he wants to verify such points as the posture of a man at the tiller or the movement of a sail in the wind. By its means the artist has his models, both animate and inanimate, almost constantly passing before his eyes.

With the exception of an interval of several years in the earlier part of his professional career, when he had a studio at St. John’s Wood, Mr. Wyllie has spent his life near the sea. Brought up at Wimereux, near Boulogne, he swam, rowed, and sailed with a fearless pleasure from early boyhood; at fifteen he built his own boat, and since then has always owned some kind of craft. Mrs. Wyllie shares her husband’s enthusiasm, and their honeymoon trip across the Channel, about twenty years ago, was made in a fifteen-foot gig. She has been his companion in nearly all the adventures which have befallen the artist on the water–when the Four Brothers had to be run to Margate for shelter from a terrific gale and there got beached, when smaller craft have capsized–as in the foregoing sketch, “An Incident at Brighton”–and when a prolonged calm has brought about famine on the sea. Winter on a barge, even though it is as comfortably equipped as the Four Brothers, obviously has perils and hardships before which the spirit of a mere sea-painting landsman would quail.

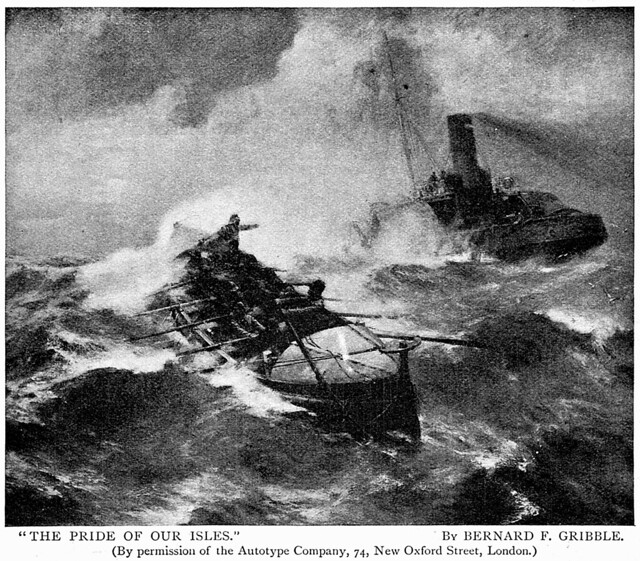

The influence of Mr. Wyllie is to be discerned in some of the work of Mr. Bernard Gribble. But Mr. Gribble, although little over thirty, has begun to assert his own individuality as a painter of the sea. He has been particularly successful with one or two pictures of the lifeboat and her mission, notably in “The Lifeboat and Her Crew” (1899) and “The Pride of Our Isles” (1902). Unfortunately, this latter picture did not make its meaning quite clear to the general public. The lifeboat is not proceeding to the rescue of the other vessel in the picture, as was supposed; this is a tug, and the lifeboatmen, almost exhausted in their endeavour to reach a wreck against wind and tide, are signalling to her their desire to be towed. Tugs not infrequently render such service, and it was an actual incident of this kind off the south coast which led Mr. Gribble to paint his picture. Its title thus refers to tugs as well as to lifeboats. Mr. Gribble took care that his meaning should be plain to seafaring eyes, although he was not unprepared for misunderstanding on the part of landsmen. Before the picture left his Chelsea studio he submitted it to the judgment of the first intelligent sailor he could get hold of. The man was asked what he thought the picture represented. He gazed at it intently for about half a minute, scratched his head, and then in sailor-language described just such an incident of the sea as Mr. Gribble had witnessed in the Downs.

The son of the well-known architect of the Brompton Oratory, it was intended that Mr. Bernard Gribble should follow his father’s profession. But his father’s work in connection with the Armada Memorial took him to Plymouth for a time, and there the lad’s fancy led him to sketch ships and the sea whilst attending the local school of art. Even then, however, Mr. Gribble’s career was not determined, for a year or two later he was studying music in Brussels, and his musical ambition was only thwarted by a pistol accident which injured his left hand. Then came more training with pencil and brush in Belgium and France. His first picture–“A Ship on Fire”–was hung at the Academy in 1891, when he was only eighteen, and he has exhibited marine pictures there every year since, besides doing a great deal of black and white work. As I have indicated, Mr. Gribble has his studio in London, but he is constantly at the coast, and, aided by careful studies, his memory of the form and colour of waves and ships is true and vivid.

Like that of Mr. Napier Hemy, the art of Mr. Thomas Somerscales is based on a large amount of personal knowledge of the sea. But Mr. Somerscales has won recognition as a painter of great power without having had the advantage of any technical training in the use of brush or pencil. Apart from a little assistance in his boyhood from his father, a shipmaster who whiled away the tedium of long voyages by sketching, and from an uncle, who was an amateur painter of some talent, he is entirely self-taught. At the age of fourteen Mr. Somerscales began training as a schoolmaster, and at the age of twenty-one, actuated by an inherited fondness for the sea, he became a teacher in the Royal Navy. For seven years he was cruising about the Pacific, afterwards becoming a schoolmaster at Valparaiso, and then again a schoolmaster afloat. In 1878, whilst residing in Chili, Mr. Somerscales began painting seascapes and landscapes with professional intent. He was fairly successful in his new vocation, but the Chilians preferred his pictures of their mountains to his pictures of their seas. As he felt that marine painting was his true talent, Mr. Somerscales eventually returned to England, and about thirteen years ago began contributing to the Royal Academy those pictures of the sea–only a dozen or so–which have given him a steadily-rising fame.

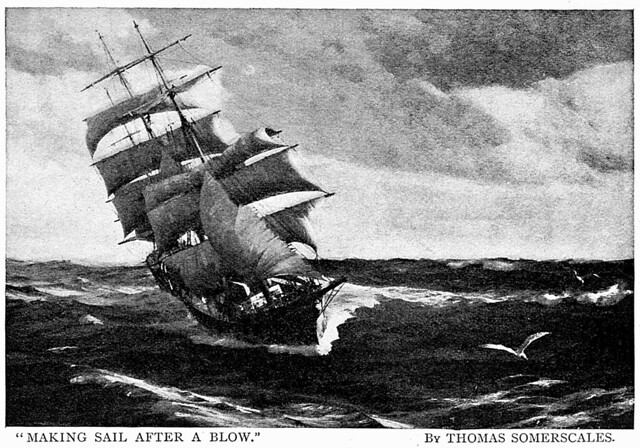

In these pictures more, perhaps, than in those of Mr. Hemy or Mr. Wyllie, Mr. Hook or Mr. Tuke, it is the sea itself, without the aid of figures or ships, which charms and interests us. In looking at “Off Valparaiso”–which was purchased for the National Gallery of British Art–“Making Sail After a Blow,” here reproduced, and most of his other principal pictures our feeling is all for the beauty of the boundless ocean, and the ship or ships appear to be merely incidental details and receive only secondary consideration.

How does the painter produce such an impression? Mr. Somerscales, who resides at Hull, amidst the shipping of the prosperous port, in explaining his method to me, said that “it must, of course, be plain to everyone that there can be no copying the sea as we copy the model or drapery. I find that I must have my memory stored with impressions which have become fixed through long study, and I endeavour to reproduce these.

“Of course,” continued the artist, “for the ships or boats introduced I have models to ensure accuracy in the drawing, but the ship as a whole has still to be the record of an impression from the real thing.”